Aan Tiwari honoured with Best Child Actor award for Baal Shiv

Aan Tiwari honoured with Best Child Actor award for Baal Shiv Ghategi rahasymayi ghatnaye!

Ghategi rahasymayi ghatnaye! Amazon Prime Video unveils the 2021 Festive Line-up; brings a heady mix of Indian and International titles on the service

Amazon Prime Video unveils the 2021 Festive Line-up; brings a heady mix of Indian and International titles on the service Release: Music video of, Yeh Haalaath, from Mumbai Diaries 26-11

Release: Music video of, Yeh Haalaath, from Mumbai Diaries 26-11 Bhumi Pednekar feels she shares feel-good value with Akshay Kumar on screen

Bhumi Pednekar feels she shares feel-good value with Akshay Kumar on screen

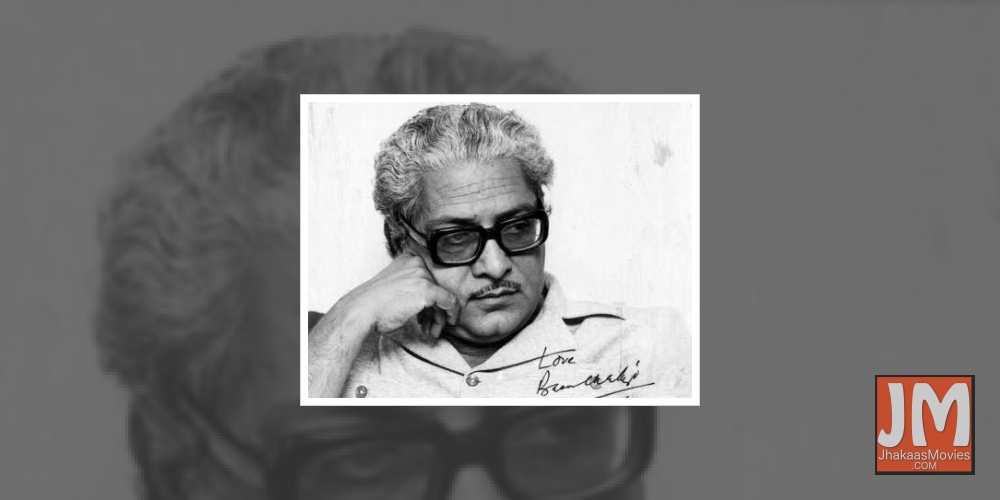

'Rajnigandha' producer Suresh Jindal: Basuda lit the path for me to the industry (FIRST PERSON)

(Basu Chatterjees 1974 release "Rajnigandha" was way ahead of its time in imagining relationships and the female protagonist, as a Bollywood romantic drama. Producer Suresh Jindal looks back at how he came to be associated with the project, as well as the initial problems he faced in releasing the film, which is considered a gem of Hindi cinema today)

BY SURESH JINDAL

Rajnigandha, like everywhere else, was running to packed houses at Metro cinema in Calcutta. I was sitting at my nephew's office in Calcutta when he got a phone call that left him speechless. I asked him what has happened.

"Chachaji, it was the Rajshri office (distributors of the film) saying that Rajnigandha has got the Filmfare Award for the Best Film...

"It CAN NOT BE. The whole industry knows that for Filmfare Awards all winners buy copies of the magazine and nominate themselves, since it's voted by the readers. We have not FILLED A SINGLE FORM... so how can it be? Send someone immediately to buy today's Times of India. I CAN"T believe it. You HAVEN'T been filling any forms behind my back, HAVE YOU??"

It was a long journey before the film saw release, after two painful years of rejection by distributors, when Rajshri bought it. Some would shout on the phone: "KAUNSA GANDHA?" because my sales pitch voice was so low and defeatist. Many said: "Naam badal do." To which they got a firm no. One even said: "Hero badal do. Hum aapko dubara banane ka paisa denge." I am known as a man with a furious temper and gave him my choicest Punjabi and California abuses.

I had just returned from America, after 11 years, with a degree in electronics engineering and five years' work experience in the aerospace industry, having last worked in Mountain View, then a little hamlet, near Stanford University, that gave birth of Silicon Valley.

Being the first foreign-returned youngest son of a Punjabi bania family I was expected to become the next mega Indian industrialist after the Tatas and Birlas.

The next thing in "electronics" in India at that time was manufacturing tape recorders. Since I wanted to set up a factory in Faridabad, license had to be obtained from the Haryana Government in Chandigarh. After multiple trips there it dawned on me that without a bribe nothing moves in our Socialist Republic.

After one of my trips to Chandigarh, I exclaimed to brother Ramesh, who had a factory in Faridabad: "Bhai Saheb, this officer kept asking me for a diary. I can't figure out why he wants a diary IN JUNE? Aren't they normally given out in December of the previous year?"

"You idiot", he guffawed, "He's asking you for a bribe".

I was miserable and did not want to become ANY industrialist. Forget about being the next mega one after the first two.

Being the roommate of a Graduate School student at UCLA's film school, I had become an addict of art cinema of the world being shown in makeshift cinema halls, improvised in shops gone bust, that had sprung up near the campus on the eve of the Hippie Revolution. Seeing the magic on the screen of humanity's great masters -- De Sica, Bergman, Ray, Kurosawa, Bunuel, Goddard and La Nouvelle Vague et al -- became a compulsive fix after struggling with quantum equations all day.

The Film Finance Corporation-financed Indian new wave had just started. It was with great interest that I would read reviews of films like Bhuvam Shome, Uski Roti, Sara Akash et al.

I had just got thru reading the review of Piya Ka Ghar in Times Of India, when Vijay Rahi, who I had never met before but whose sister Veena was a friend of my older brother Ramesh, dropped in to see me. He had come to persuade me to become a distributor of the new wave films. (the Delhi flat, where the film was shot, was their house in Defence Colony. I can never forget their kindness).

I picked up the Times Of India with the Piya Ka Ghar review, opened it and asked "Do you know this Director?"

"Arre, yeh toh hamare bahut acche dost hain."

"Vijay, I will not distribute films but if this gentleman agrees, I will produce a film with him. When you go back to Bombay, kindly ask him, and I will produce a film with him."

I was called to Bombay to meet Basuda. I found him to be extremely pleasant and friendly. He gave me the Treatments of three films he wanted to make. After reading them all, I liked the one based on Manu Bhandari's story Yeh Such Hai.

Next morning we met at his flat in Prabhadevi and I told him my choice. Basuda hesitated and asked: "Mr. Jindal are you sure you want to make this one?"

"Yes Sir. I am sure. Why do you ask?

"Because two producers have already given me a signing amount on this, and never came back. May I please ask you why you want to make it?"

"Sir, our society is so conservative that for a girl, who is already engaged, to even mention another man's name, makes her a "fast girl" and a vamp of low character. The story has a liberating aspect that our country needs now."

I was, in my last years in America, an electronics engineer by day and a full blown California hippie at night, right from when the party started. I was appalled by the conservatism of our society and wanted to liberate it.

I reached into my shoulder bag, took out my book of travellers cheques, and gave Basuda the signing amount. I could see the puzzlement and amusement on everyone's face as I said: "Sir, just deposit them in the bank like regular cheques."

In two days' time, after I had given signing amounts in travellers cheques to KK Mahajan, the cinematographer, Narinder Singh, the sound recordist and other crew, there was amusement in the industry of this weird producer in jeans and boots, surplus army shirt from a Salvation Army Store in California and a sling bag, who is paying everyone in this unheard-of way. And spoke Hindi and Punjabi with an American accent to boot.

The journey had begun that would bless me to produce other classical and landmark films.

It was the warmth, integrity, humour of the legendary talent of Basuda that lit the path for me to the industry. I humbly offer him my shraddhanjali.